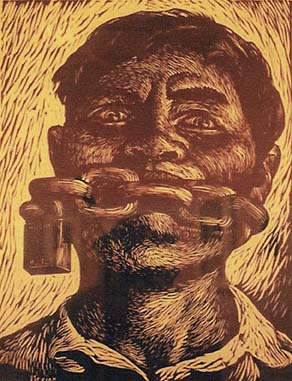

Braceros Waiting for Contracts to go to the U.S, (linocut, 1972) by Alredo Salce.

Current Issue Highlights More Readings DA Home About Direct Art

The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum

By Bob McCray

Braceros Waiting for Contracts to go to the U.S,

(linocut, 1972) by Alredo Salce.

The Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum (MFACM), the largest Mexican or Latino arts institution in the U.S., with a collection of over 3500 works including paintings, prints, photographs, sculpture, and artifacts, may be said to exemplify both statements.

The museum’s permanent collection (presented chronologically from the pre-Cuauhtemoc era of Indian and Aztec cultures, through the Spanish Colonial period, the struggle for independence, the Mexican Revolution, and the post-revolutionary and U.S. period) features classical and contemporary artists, internationally famous and those unknown outside of Mexico. Self-taught artist Mardonio Magena is one recent "discovery" (largely unknown outside of Mexico). His "Grinding Corn," (Ca. 1938) a rough-hewn woodcarving of a mother and child, is displayed with early Indian art, and is representative of his carvings of rural farmers. A show of his sculpture has traveled throughout Mexico, and a book on his work has been recently published. According to Cesareo Moreno, director of visual arts and curator, "He was never given his due. In the next 10 or 20 years, he will finally get his niche in Mexican art. We have 13 of his works, and didn’t know how valuable they were." Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera collected his carvings. Rivera said, "Mardonio Magana, Campesino, is the greatest Mexican sculptor." The museum will host a solo exhibit in future.

Another museum masterpiece is "The New Awakening" (2003), a spiritual piece made by the Huichol Indian tribe in the western Sierra Madres mountains. "It’s made of over one million ceremonial chaquira beads and tells the story of sacred rituals, the rain gods, and the use of peyote in religious rituals," says Moreno.

The Spanish Colonial rooms, reveal the spiritual feelings of the people during the 300-year period (1519 to 1810), when life centered around the Christian and agrarian calendar. Nineteenth century paintings of Saint James the Elder, Saint Luke The Evangelist, and the story of Sister Juana Ines de la Cruz, one of Mexico’s greatest writers (the "Tenth Muse") are featured. The museum commissioned a Retablo sculpture and painting by Alejandro Garcia Nelo (2000), to recreate an ensemble found in many Spanish churches in Mexico. "It works like stain glass windows, teaching the stories from the bible to an illiterate audience. The twist was that we asked the Mexican artist to tell the story of the spiritual conversion," says Moreno. The left panels portray the Pre-Cuauhtemoc spirituality. The right panels depict Spanish Catholicism, and the spiritual syncretism is represented in the center.

Feelings of pride and respect for courageous leadership are engendered by busts of Father Miguel Hildago and Jose Maria Morelos (Aurelio Agustin Arredondo, 2000, 2001), which highlight the struggles against Spain (1810-1821), while a bust of Benito Juarez (Augustin Arredondon Ranzel, 2001) highlights the pre-and post-French struggles under Maximilian (1858-61).

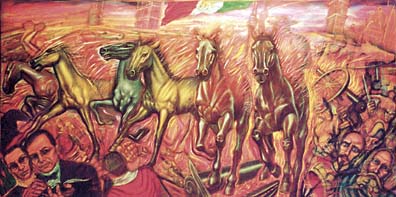

The "Battle of Puebla," an oil painting by Alejandro Romero (1987) portrays the victory of a small band of Mexican soldiers against a larger French force in 1862, celebrated as Cinco de Mayo. "This was picked up and is celebrated more in America than in Mexico, because Mexico won the battle, but lost the war," says Moreno. Mexico celebrates Independence Day (from Spain) on the 16th of September.

Some of the most well-known examples of what some might consider "Art as propaganda" came later, born of the economic and political programs of President Porferio Diaz, and other latter-19th century Mexican presidents, when Indians and farm workers were exploited by large companies, and when, in 1910 on the eve of the Mexican Revolution, only a few hundred families owned most of the land in Mexico.

"During the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1921, all the people of Mexico left their homes and towns and traveled across the country to fight," says Mareno. When they returned home, after seeing other towns and villages, an education of the masses had taken place that solidified Mexican culture. That later became known as Mexicanidad.

"After the revolution, two artistic movements, the printmakers and the muralists, took it as their mission to celebrate the culture and history of Mexico and educate the people."

Museum rooms convey this culture and history. The "Tierra y Libertad" room is devoted to Emiliano Zapata, one of the heroes of the Mexican revolution who fought to return the land to the villagers.

"Leopoldo Mendez was one of the premier printmakers to come out of the movement," says Moreno. Two museum prints— "The portrait of Zapata," (1948 linocut), and "The Assignation of Zapata," (1950 linocut) — exemplify his mastery and demonstrate the power of graphic arts. A member of the League of Revolutionary Artists and Writers (L.E.A.R.) and contributor to its periodical "El Machete," he founded The Workshop of Popular Printing. Mendez attacked the treatment of the rural poor. MFACM holds the best collection of his prints in the nation. (Also, Hugo Brehme’s large, sepia-toned studio photograph of "General Zapata, chief of the southern armies," (1910) presents his imposing, young figure in his finery— sombrero, pistol belt, and embroidered jacket.)

Printmaking was commonly used in Mexico for social protest. Prints could be easily mass-produced for wide distribution. A more recent example of the power of graphics is Adolfo Mexiac’s "Freedom of Speech," a head bound with a chain around the mouth. "In 1968, at the time the Olympics were held, there was a student protest in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Mexico City, and armed troops of the government killed students and annihilated the student movement. The print is easy to understand. You can see the pain in the eyes. It’s used in Latin America as a symbol of protest and revolt," says Moreno.

Meanwhile, the most well known of the muralist movement artists were Jose Clemente Orozco (1883-1975), Diego Rivera (l886-1957), and David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), who painted murals of the revolution on walls of public buildings.

Prints of Rivera and Siqueiros are featured in the room adjoining the Zapata hangings. "While Rivera was an incredible illustrator, in Siquieros you see modernism in every sense of the word — the brush stroke and use of painterly vocabulary that was coming out at the time." Sequeiros served as a soldier, diplomat, union organizer, and L.E.A.R. activist. "His color lithograph ‘Christ,’ exemplifies the modernism of his work," according to Moreno. "This is very typical of the Christ figures in Puebla, Mexico, which were known for showing the bloody, Good Friday, crucified, suffering Christ with skin hanging off the ribs. It has a connection with the violence of the pre-Columbian gods who wanted sacrifice — people skinned alive and their hearts taken out — versus the U.S., where the Christ of Easter is risen and triumphant."

On an adjacent wall are three untitled works of Diego Rivera, an ink-on-paper of children (1949) along with an untitled graphite-on-paper (1955), and an untitled crayon on newsprint (1945). Rivera, the most publicized Mexican painter of his era, was born in Guanajuato, studied in Europe and returned to Mexico in 1921 to become a leader in the muralist movement, redefining the Mexican heritage and breaking free from the constraints of classical European art. "These were drawings from his sketch books," says Moreno. "He was famous for drawing everyday people. These drawings were then used in the murals. People knew what they were looking at and could appreciate their own culture, because they could see it celebrated in art."

Meanwhile, the works of Rivera and Siqueiros are juxtaposed with "Legend of the Volcanoes" (1940) a large oil on canvas about "love" by commercial artist Jesus Helguera. It may be the most reproduced Mexican art work, appearing on calendars throughout Mexico year round. "It wasn’t intended for display," says Moreno. "When we tell visitors from Mexico this is the original, they say, ‘No!’ Then they see the signature. Now it’s on murals, restaurant menus, T-shirts, and cars. It’s an icon with a life of it’s own." The painting tells the story of the origin of the two volcanoes, Popocateptl and Iztaccihuatl, in view of Mexico City. In the painting, Popocateptl, the warrior, in love with the Aztec princess, Iztaccihuatl, returns from battle to find her frozen in sleep waiting for him. He carries her to the mountains where they turn into the sleeping and smoking volcanoes.

"Retablo" by Alejandro Garcia Nelo (2000)

portrays

pre-Cuauhtemoc spirituality, Spanish Catholicism,

and the spiritual syncretism.

Jean Charlot, who was born in 1898 in Paris and moved to Mexico in 1921, actually created the first true fresco murals in Mexico in 1922. Orozco, for example, followed his lead. Charlot’s color painting depicting warriors in full regalia, as found on a bench at the Temple of Warriors in Chichen Itza, is the museum’s "cornerstone." Charlot, a prolific artist and writer, promoted Mexican art in the U. S. and Mexico, including the engravings of Jose Guadalupe Posada.

The Virgin of Guadalupe "section," is composed of art works of U.S. Artists. "The Chicanos embraced the icon as a symbol of hope for a disenfranchised people," says Moreno. "The image is the most revered of Mexican icons, a symbol of spiritual power from a 500-year religious tradition." Moreno notes that as a symbol of strength and hope, "it has been both adopted and adapted." The symbol has been carried by picketing farm workers.

It’s not unusual that Tolstoy and Diego Rivera, coming from different cultures, held seemingly dissimilar viewpoints on the purpose of art, and that, depending upon the perceptions of the viewer, examples of both interpretations might be found in the museum’s permanent collection. Still another visitor might conclude that the two perceptions are not at odds, but one and the same — that the yearning for social justice may be one of man’s "highest and best" feelings.

The museum hosts six changing exhibits each year, which have included Frida Kahlo, Gunther Gerzso, Mexico’s most famous abstract painter, and an annual Sister Juana festival.

MFACM is located at 1852 W. 19th Street, Chicago, 60608 in the

Pilsen/Little Village community. Contact 312-738-1503. Open Tuesday through Sunday, from

10 a.m. to 5 p.m. www.mfacmchicago.org

Current Issue Highlights More Readings DA Home About Direct Art